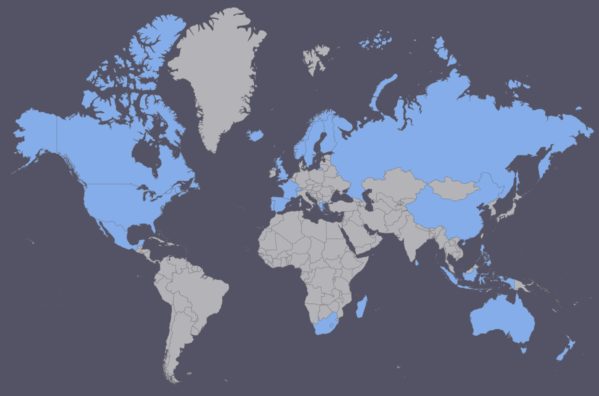

No, we have not traveled to Western Australia. But Jamie’s a little under the weather this week and things are slow between Christmas and New Years, so I’m reliving a few tales of travel past that have never been told on JimandJamie.com:

According to Google, it is 747 miles from Ceduna, South Australia to Norseman, West Australia. What Google doesn’t tell you is that they are 747 very long, ugly miles.

Google also says it takes 12 hours and 28 minutes to drive from one to the other. But they don’t tell you is that there is nothing — absolutely nothing — between the two except flat, ugly outback that’s been been baked black by millions of years of unrelenting sun.

Do not mistake the names on the map above — Cocklebiddy, Balladonia, Madura, Mundrabilla, Border Village and all the rest — for cities or towns. They are merely wide spots in the road where you can fill up with gas, get a crusty meat pie that’s been heating under a lamp for several days past its expiration date, or buy a bottle of much-needed water before you wearily climb back into your car to begin the next leg of your journey across this wasteland.

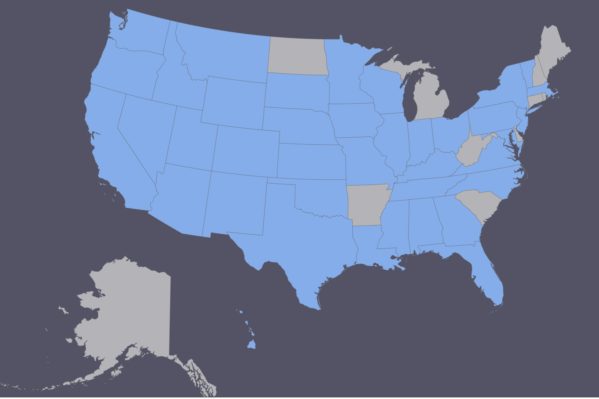

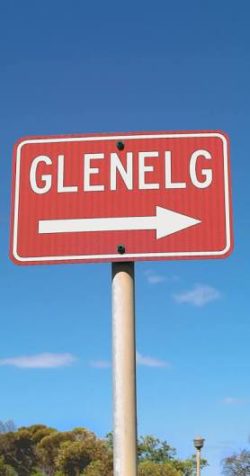

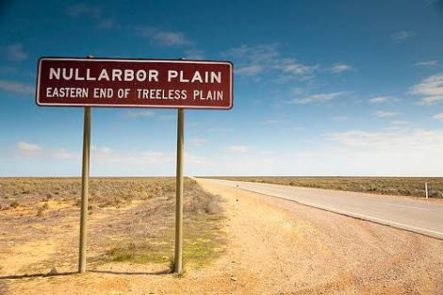

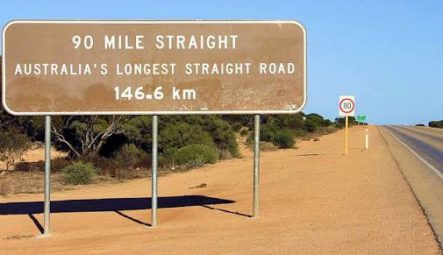

There are no sights to be seen. No roadside attractions to visit. No historical markers of any kind. The only points of interest are a few road signs like these.

The word Nullabor is a bastardized version of the Latin words for “No Trees” (null arbor). And as you can see in the photos above, it may be a bastardization, but it’s not inaccurate.

I had hitchhiked across Australia on my first trip here after I graduated from college. In those days the 400 miles between Ceduna, South Australia and Eucla, Western Australia were unpaved. It often took days for hitchhikers to thumb a ride from one end of the godforsaken Nullabor Plains to the other, but when you finally did get a ride you knew it was going to take you all the way across, simply because there was nowhere for anyone to stop along the way. I ended up hitchhiking back and forth across the Nullabor four times.

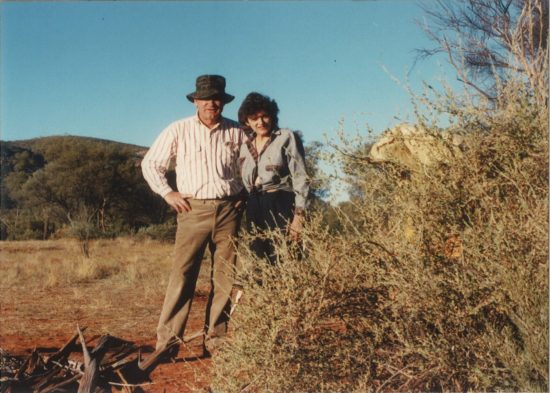

The first time Jamie and I came to Australia, I wanted to drive across the Nullarbor again just to see how it had changed. I’d heard that the road had been paved and the images I’d conjured up in my head turned Cocklebiddy and all the rest of those horrid little spots into beautiful oases in the desert.

Jamie, always the good sport, said, “Sure, if you want to drive all the way across the country to Perth, let’s do it.”

To make a long story short, the pavement is the only thing that has changed along the Nullabor. Cocklebiddy, Mundrabilla and all the rest are still horrid little spots where you can stretch your legs, and get one of those rancid meat pies (in fact, I suspect that they may still be the very same meat pies) and a bottle of water. Oh, sure, some of the petrol stations are new and now offer ice cream bars and cartons of iced coffee and bags of chips, but they are not places any rational person would want to visit.

A motel or two can be found along the way, but I knew that my princess wife would find them wholly inadequate. My theory was that we needed to drive all the way to Norseman, the first real town on the west side of the Nullabor, if we expected to find a nice motel.

So I did a little research and found the nicest hotel in Norseman. But in retrospect, that’s a little like looking at yourself in the mirror and wondering, “Which of these warts is the prettiest?”

First of all, Norseman was even worse than I remembered it. At dinner, I asked our waiter how the town was doing economically.

“Not very well,” he responded mournfully. “The mine closed down and one third of the people moved away. So the company that owns the mine picked up their houses and moved them to another town.”

Seriously. They picked up one third of the town and moved it somewhere else. Even houses don’t want to live in Norseman.

We checked into our motel and took our bags to our room and the moment we opened the door, Jamie opened her mouth. She hated everything about the place — the bathroom, the bedroom, the bedspread, the carpet, the shower, even the material they used to build the structure.

I blame her extreme reaction on her dear departed stepfather, Dawson, who proudly encouraged her to settle for nothing less than the best, a rule she clearly violated when she married me. Jamie is a sweet, caring, kind woman who became the Frankenstein version of Eliza Doolittle. She learned to settle for nothing less than the finest meals, the finest hotels, the finest cars.

So it’s no wonder that she was horrified by our Norseman accommodations. On one hand, I can’t blame her because I wasn’t exactly delighted with them, and on the other hand I figured, It is what it is and we’re only going to be here overnight, so what the hell.

But Jamie wouldn’t let it go. The way she carried on, you would have thought that she had been sentenced to house arrest in this weary, dreary motel. She was eager to show Dawson the godawful conditions she was forced to endure for eight long hours, so she began taking photos. It sounded like we had been discovered by the paparazzi.

Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click. Click.

Photos galore.

When we got home Jamie immediately took those rolls of film down to the corner drugstore to be developed. I was with her a few days later when she picked them up. With a bit of a mad glint of victory in her eye, she tore open the envelope and began flipping through the photos. This is what it sounded like:

Flip.

”Crap.”

Flip.

”Crap.”

Flip.

”Crap.”

And so on and so forth. You get the idea.

Why was she so upset? Because the photos were absolutely beautiful. Stunning. She couldn’t have created such gorgeous images if she had tried. Each of those Kodachrome works of art made our shabby stopover look look like the most beautiful hotel in the world. The lighting was perfect. She made the mistake of shooting her photos during the period of time cinematographers call “The Golden Hour,” that brief time in the blur between afternoon and evening when the soft, natural light can turn a blind man into Ansel Adams.

So in the end, Jamie was unable to show Dawson how I had mistreated her by making her stay in a dumpy motel in a dumpy town in the middle of the Australian outback.

But the good news is that the photos were so good that they encouraged her to take up a new hobby.

Photography.

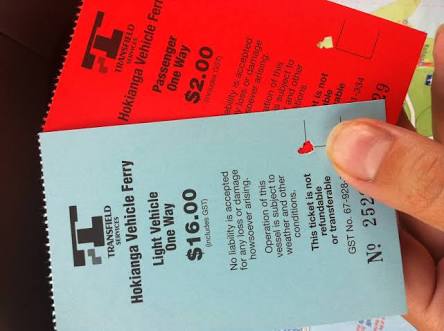

Rowena, the pretty little town on the other side of Hokianga Harbour

Rowena, the pretty little town on the other side of Hokianga Harbour

“She’sh beautiful,” he said. “Gimme a little kiss.”

“She’sh beautiful,” he said. “Gimme a little kiss.” We wanted to sleep. They didn’t.

We wanted to sleep. They didn’t.