More memories plucked from the plastic crates and cardboard boxes stored out in the shed:

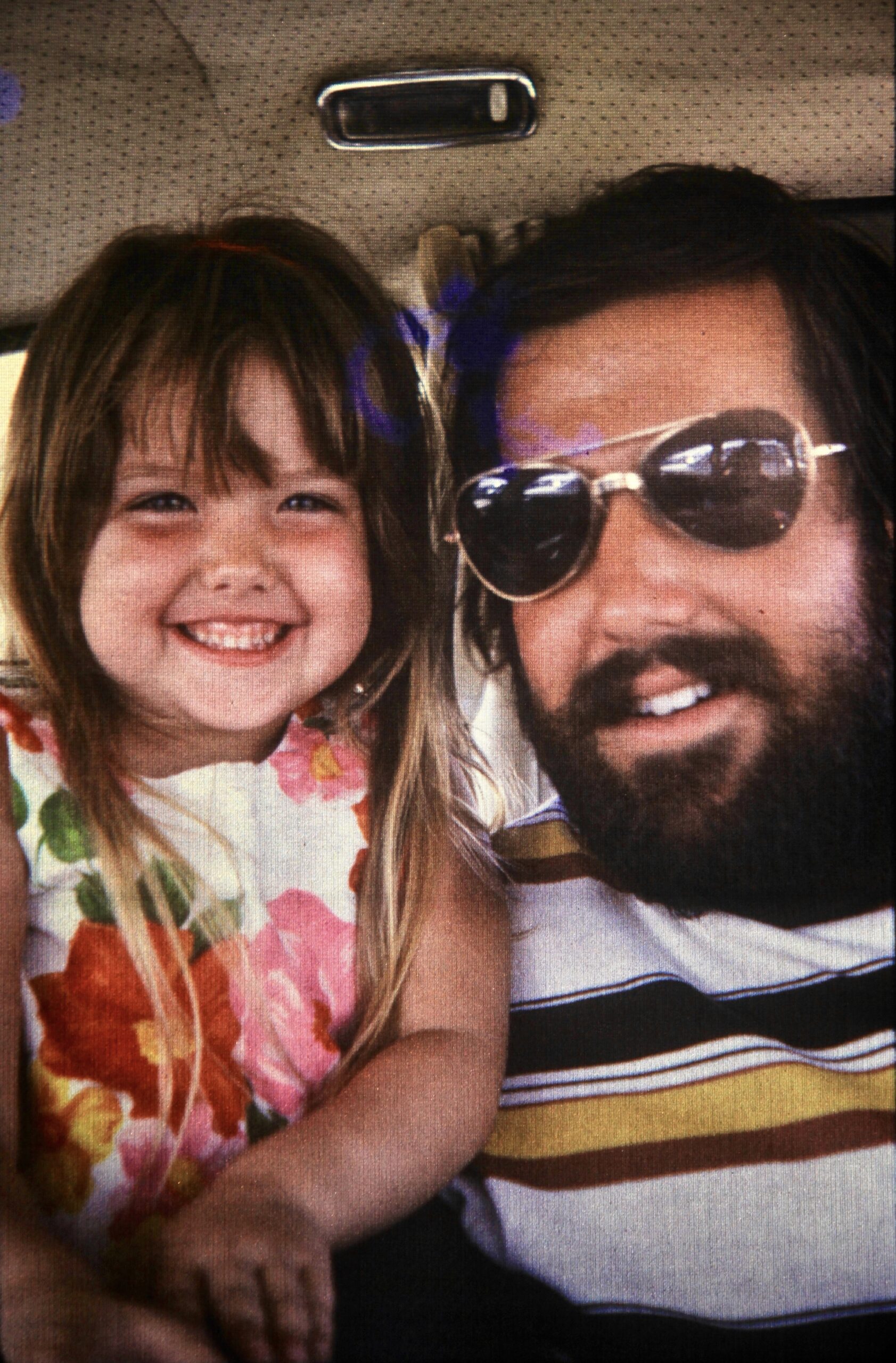

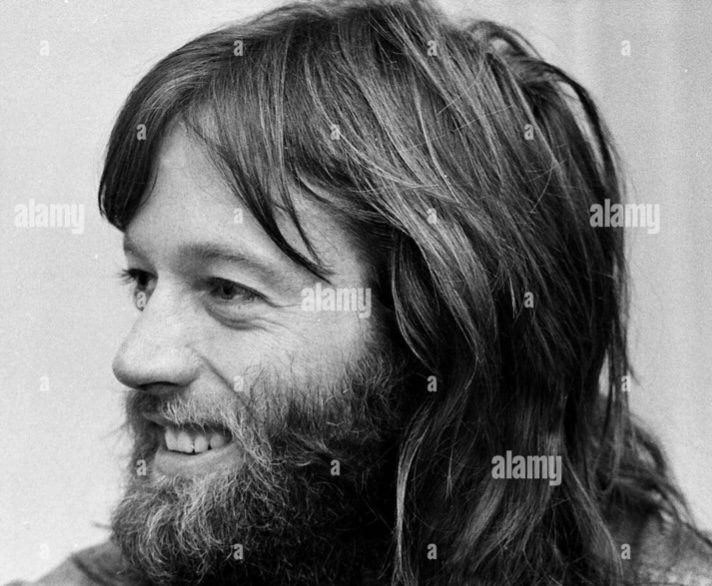

Easy Rider, starring Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Jack Nicholson, premiered about the same time I got my first job in advertising. Apparently I looked a bit like Fonda, which was not always a good thing.

He played a drugged-out hippy biker in the film and quickly became a symbol of the seventies counterculture. I worked on Wilshire Boulevard, where most of Los Angeles’ ad agencies were gathered, and when I walked down the street at lunch, construction workers looked down at me from their work stations several stories above the street, and hurled obscenities in my direction.

”Fuck you, Fonda,” was one of their favorites.

Not particularly creative, but to the point. My creative director probably would have praised it for economy of expression.

It’s not like we were twins, but I can understand how people may have confused one of us for the other from their distant perches a couple stories above the boulevard. We had similarities — long reddish brown hair, coloring, short trimmed beards, facial shapes, and lanky frames.

Fonda’s hair was better than mine, but c’mon, I clearly have a far stronger, more masculine nose. When he’s clean shaven, his lips definitely appear to be the result of some deYong-ish DNA. There are other deYongs, the ones armed with those lips, who probably look a lot more Fonda-ish than I.

That being said, I seriously doubt if anyone ever walked up to him and said, ”Hey, aren’t you that ad guy?”

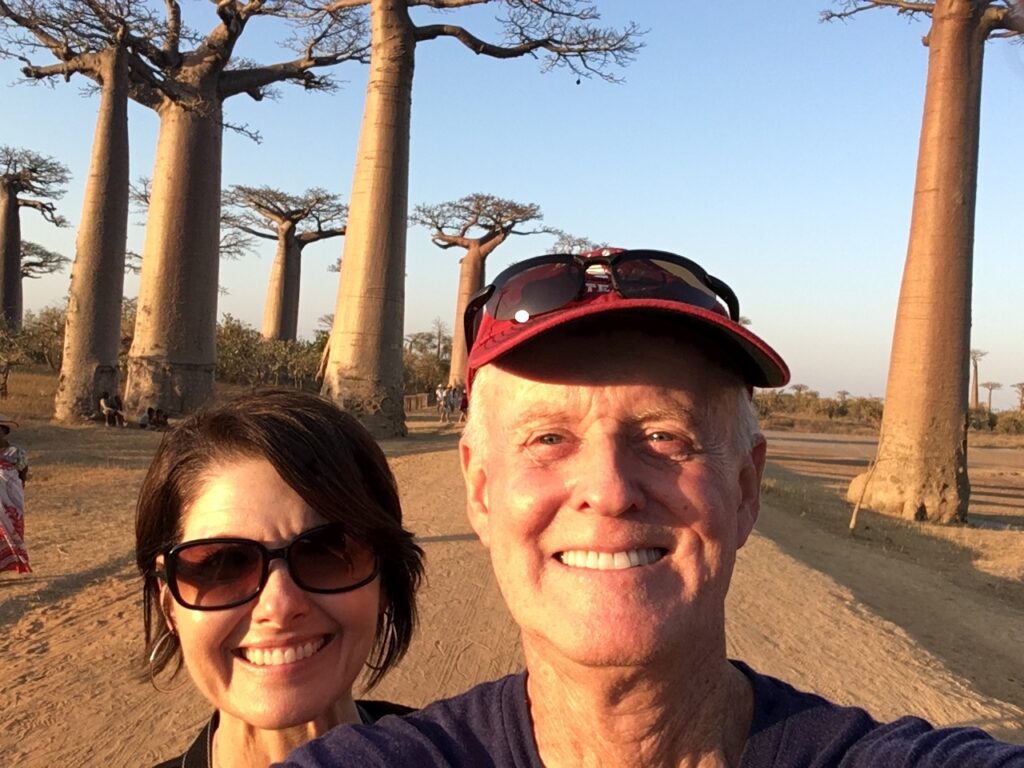

My girlfriend thought it was hilarious when strangers asked me for my autograph. She loved the look of disappointment on their faces when I told them I was not who they thought I was. When we went to see Fonda’s follow-up films, we had to see them at drive-ins because she could not contain herself. ”Ooh, ooh, ooh,” she’d squeal. “You look just like him at that angle,” and at other times, ”Nah, I don’t think you two look anything alike.”

But time is a cruel mistress. Fonda’s career foundered. Hollywood stopped calling him and construction workers stopped calling out to me.

Twenty-five years rolled by with no one saying I looked like anyone except, well, me. Truth be told, I kind of missed being mistaken for a movie star.

Then NBC began promoting a new television show named Third Rock from the Sun. It starred John Lithgow, who’d had a long, successful career as a dramatic actor but finally achieved real fame in this over-the-top comedy by playing a dim-witted alien who was baffled by human behavior and American culture.

But now instead of hearing that I looked like a handsome young movie star, people began saying I looked like this balding, middle-aged, ruddy-faced TV star. Strangers on the street once again began asking for autographs. Restaurant hostesses gave me conspiratorial winks and led us to better tables than we would have otherwise been given. I once again became aware of whispering and pointing in my direction.

The craziest incident happened in the airport in St Louis where a blizzard had grounded my connecting flight. When I went to the counter to find an alternate flight, the ticket agents refused to believe I was not John Lithgow traveling under a false ID (obviously this occurred prior to to heightened TSA security checks). They were not convinced even after I showed them my drivers license to prove my real identity. The agent upgraded me to first class on the new flight, handed me a boarding pass and said, ”Here you go, Jim,” emphasizing my first name as if the two of us were in on a grand joke that no one else understood.

One of our clients was very involved in a Los Angeles children’s charity. She invited me, my business partner and our wives to its big annual fundraiser at Merv Griffin’s Beverly Hills Hotel. It was a Hollywood-ish kind of event and a number of celebrities were in attendance. We had attended the previous year and knew that Merv, one of the charity’s biggest supporters, would once again regale the crowd with hilarious show biz stories, and that Carl Reiner, another major supporter, would also get up again and tell his own hilarious stories.

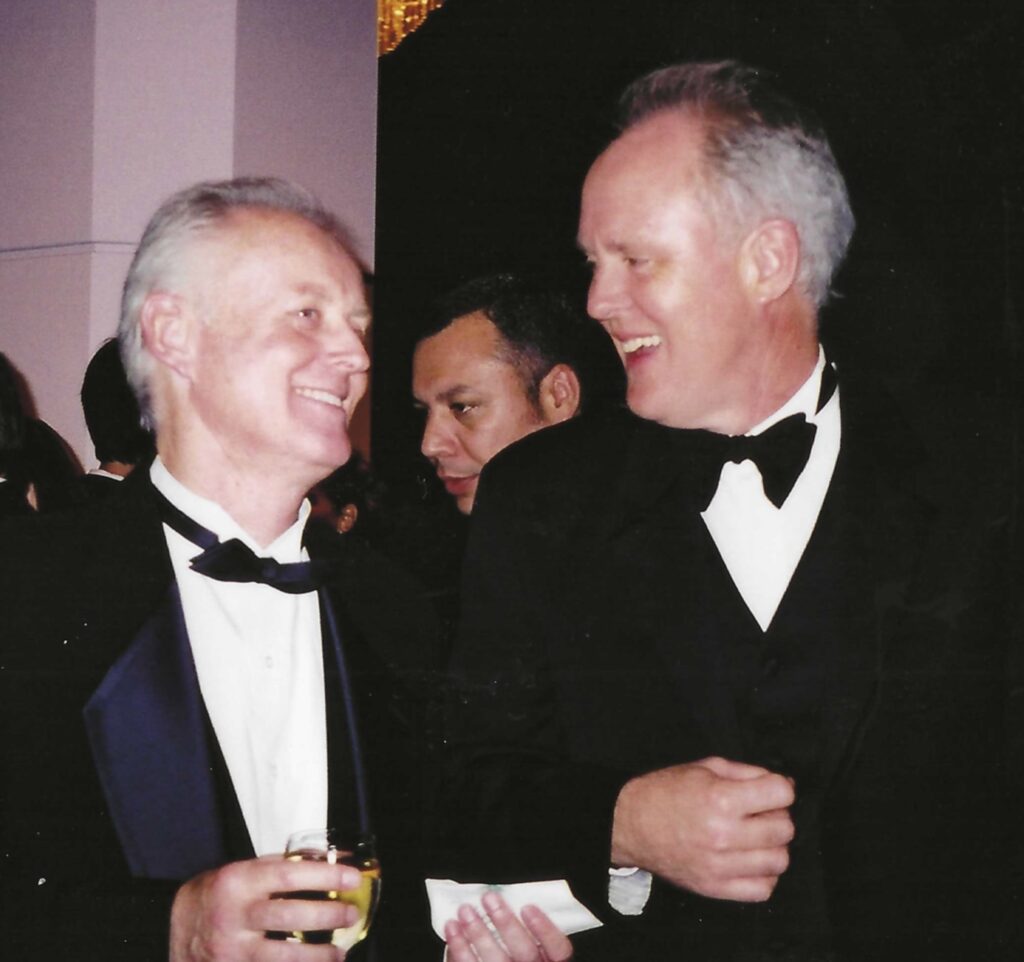

There was no way Jamie and I were going to miss the event, especially after it was announced that John Lithgow was going to receive an award and be named Man of the Year.

The event was preceded by a cocktail hour at which all the celebrities mingled and exchanged small talk with the little people (“Small talk with the little people.” Hah! What other kind of talk would you exchange with little people?) Jamie and I spotted Lithgow but stood off to one side while he spoke to a number of other people. We waited until he was alone for a moment, when all the well wishers and groupies had briefly drifted away, and then we made our move.

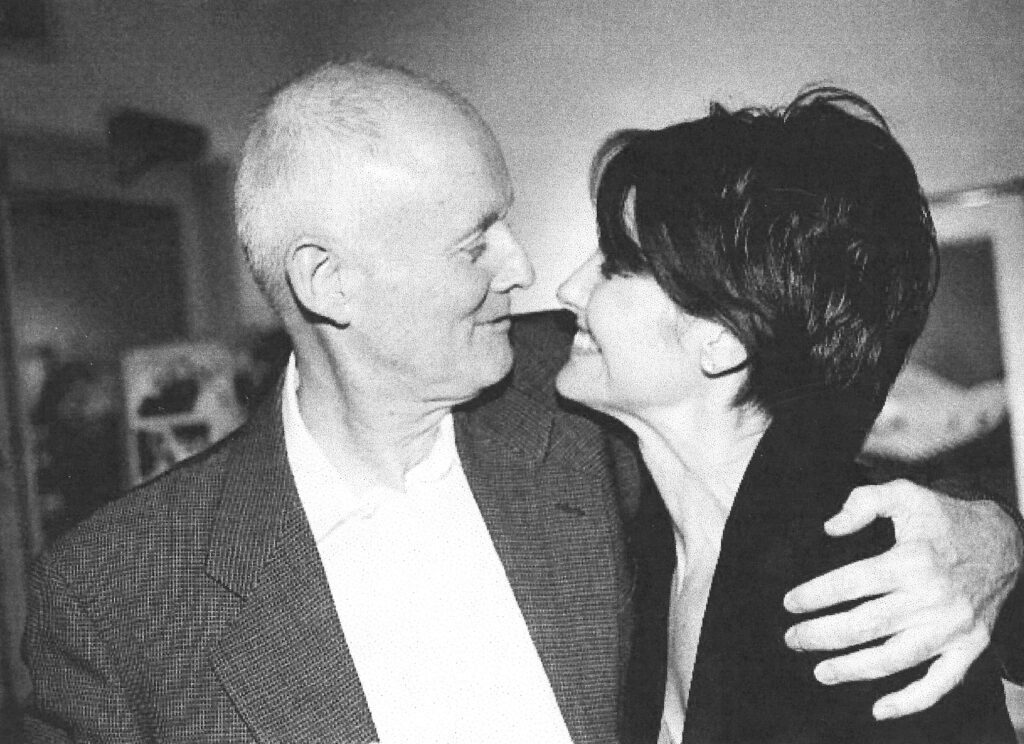

”Excuse me, John,” I said. ”Would you mind if my wife took a photo of us together?”

Lithgow looked at me. He started to speak, but stopped. He looked at me again. His face lit up. And then, with that distinctive John Lithgow delivery, he said, ”Well, yes, I can certainly see why.” Jamie took a couple shots of us looking directly into the camera, and then John said, ”Let’s do one where we’re looking at each other.”

And that, my friends, explains the photo above.

Somewhere up near the top of this story I said that time is a cruel mistress. Fame must be an equally cruel master. I just cannot imagine being so famous that complete strangers feel free to intrude on your privacy, demanding that you be included in their selfies, interrupting your dinner, or even worse, staring and pointing like you’re a monkey in a cage.

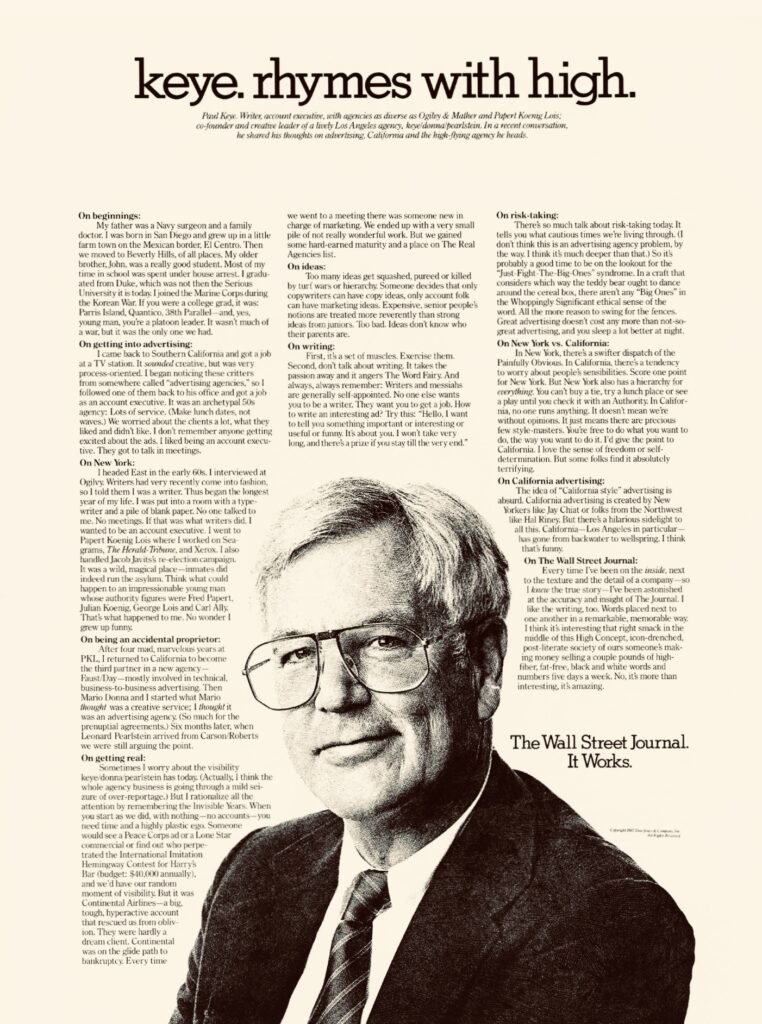

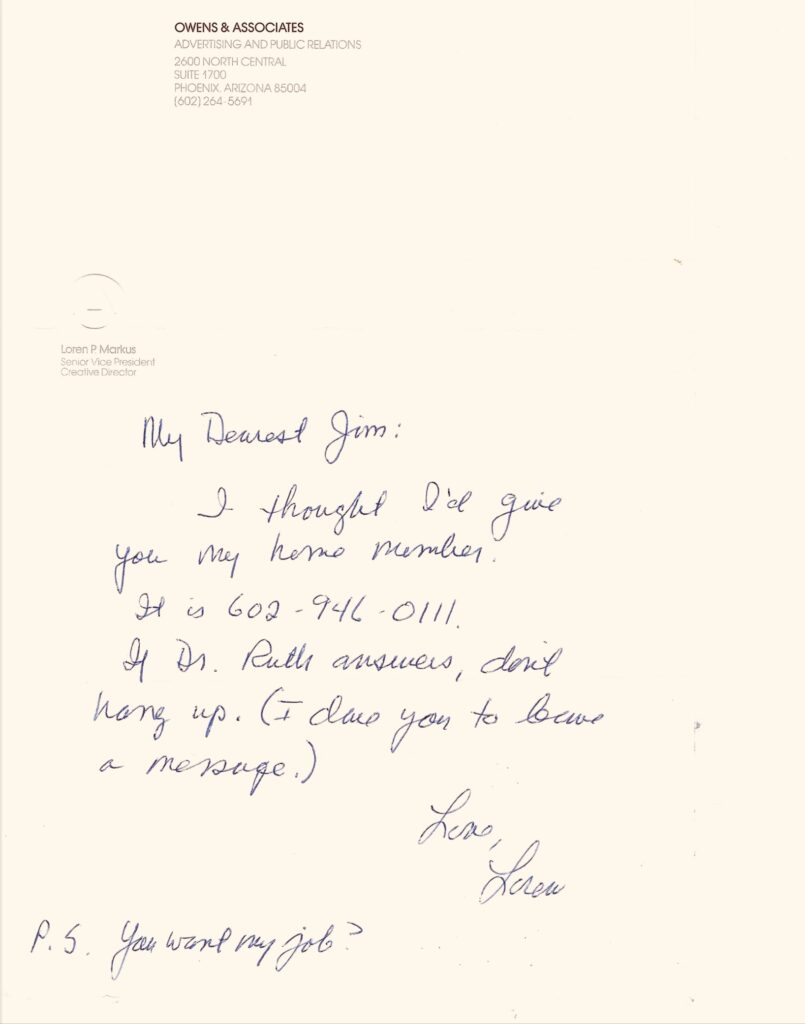

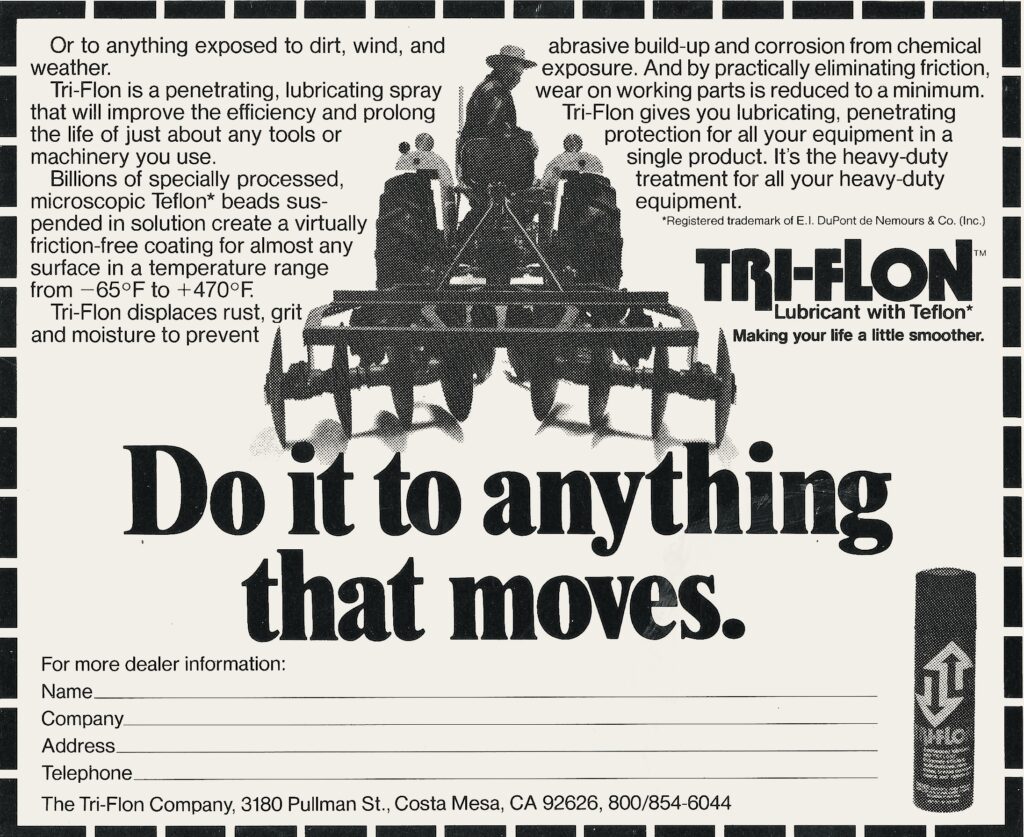

Toward the end of my first advertising career, I was the public face of our ad agency, the guy the reporters called when they wanted a pithy quote. My job was to make sure the agency got lots of publicity and that our name graced the pages of all the right publications. On the continuum between anonymity and fame, I fell somewhere in the Zone of Well-Knownedness.

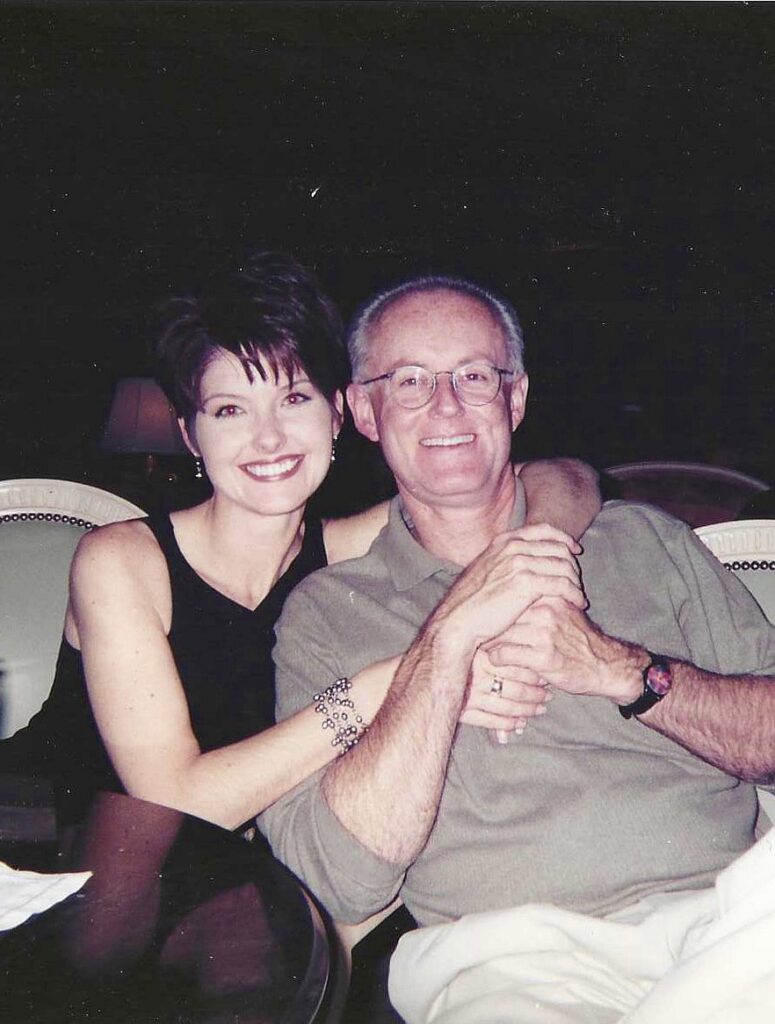

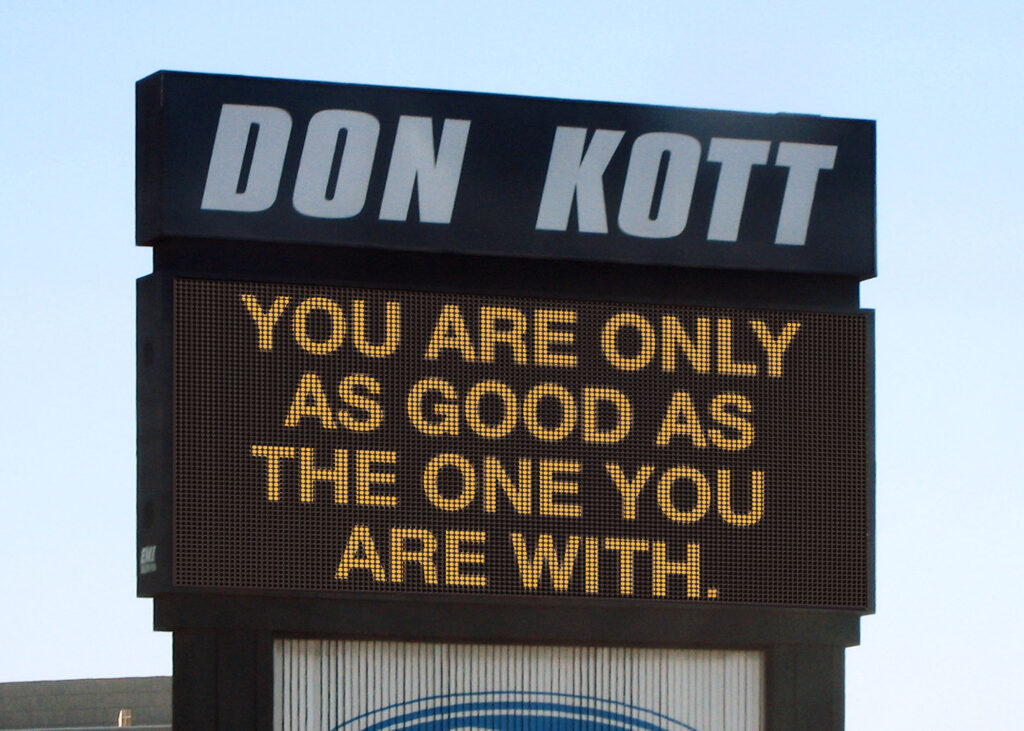

My new girlfriend joked that she had always wanted to go out with someone famous, and that I had fulfilled her fantasy by being a big fish in a small pond. Big enough and small enough that other advertising people often approached us in public just to ask if I was who they thought I was. It was low-level attention, nothing too annoying, but she quickly grew tired of it. ”We can’t go anywhere without someone recognizing you,” she said. ”I’ve changed my mind. I don’t want you to be famous anymore.”

She was right.

If my fleeting brush with fame taught me anything, it would be this:

It’s probably much better to look like someone famous than to actually be someone famous.

%$&*!

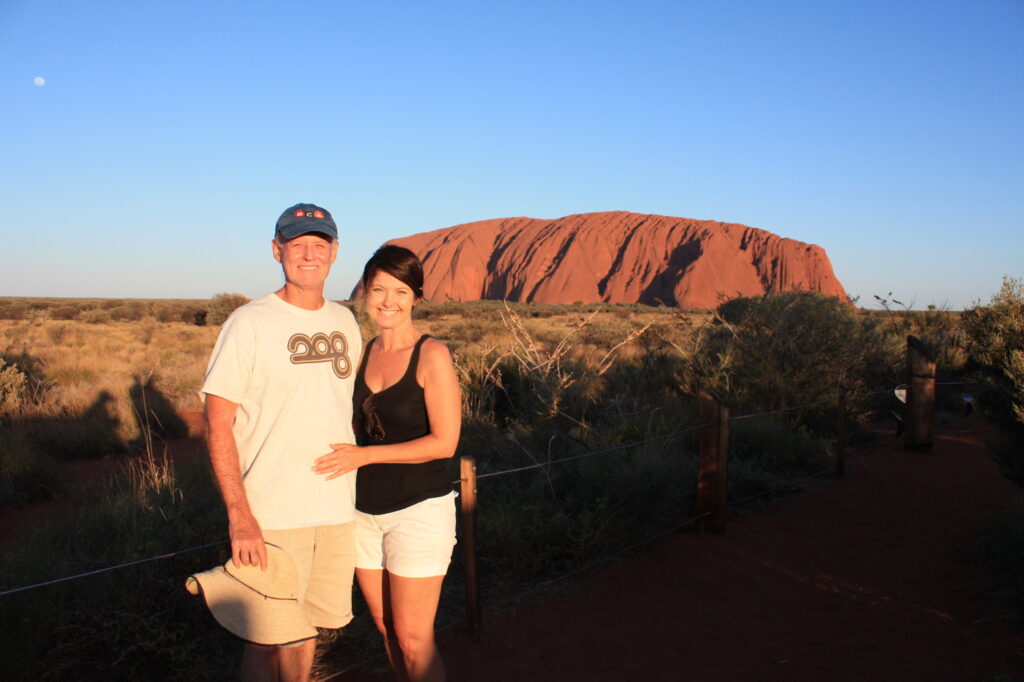

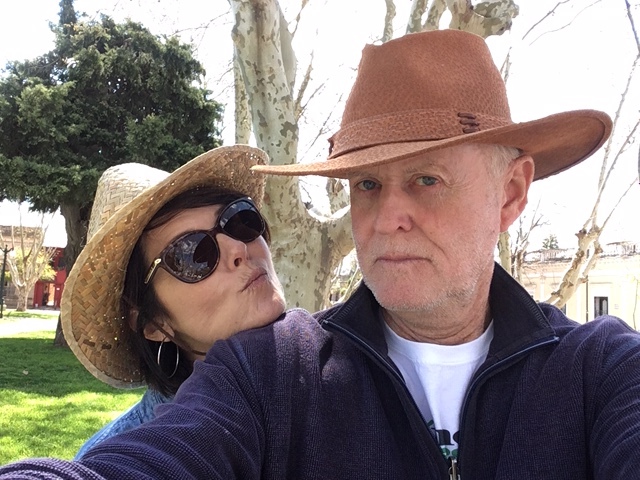

Years later, just a few months ago, Jamie and I had dinner in Santa Monica with god daughter Stella and her parents Dan and Caren. Caren got up to use the ladies room and when she came back to the table she said, ”Hey, Jim, your doppleganger just walked into the restaurant.” Sure enough, John Lithgow had been seated not too far away from us.

I stopped at his table on our way out of the restaurant. I repeated the line from the charity dinner of twenty years earlier.

”Excuse me, John,” I said. ”Would you mind if my wife took a photo of us together?”

He went blank for a moment. You could see the cogs turning as he accessed his memory banks to figure out how we knew each other. Then, BINGO, there was an obvious flash of recognition. He leaned in so that we were face to face, looked directly into my eyes, and uttered three words that made it clear he knew exactly who I was.

”Fuck you, Fonda.”

%$&*!

Only the first paragraph of that last story is true. The rest of it is a complete fabrication. We did dine in the same restaurant in Santa Monica, but I didn’t stop at Lithgow’s table and he did not say what I said he said.

But it would have been freakin’ hilarious if he had.

%$&*!

I just read an article in which former child actor Cole Sprouse said, ”When we talk about child stars going nuts, what we’re not actually talking about is how fame is trauma.” I think fame is like cocaine in the 80s. They might tell you it’s harmless, but in truth it’s horribly addictive and destroys everything it touches.