Advertising people often ask what happened to me? Why, they wonder, did I suddenly stop winning advertising awards a couple decades ago? I had been prominent in the advertising industry for a number of years, and had won truckloads of awards, and then I seemingly disappeared overnight.

The answer is really very simple: You cannot win if you do not enter. And I have not entered any competition since way back in the mid ‘90s. Here’s why:

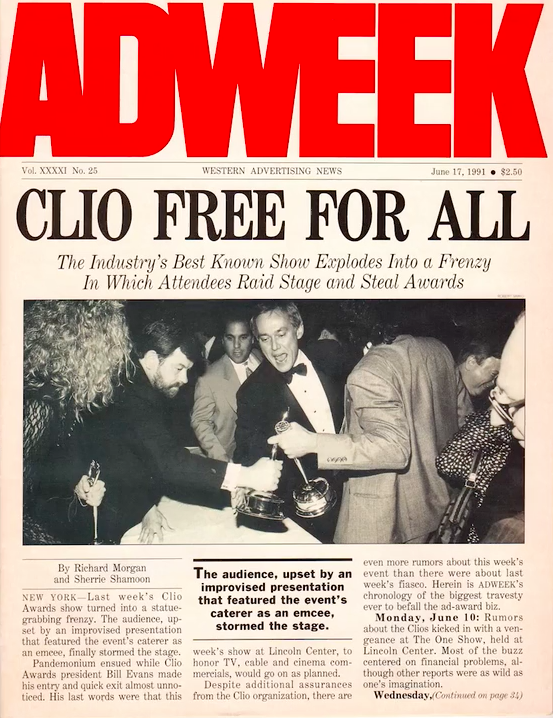

Fact is, most advertising people will do anything to get their hands on awards. Even if they are not actually deserving of those awards. Adweek (above) and the New York Post (below) explain the most egregious example:

On June 13, 1991, the prestigious Clio Awards for excellence in the advertising industry was a night to remember – for all the wrong reasons.

Unlike the dignified affairs of previous years, the banquet at New York’s Manhattan Center studios descended into what journalist Trip Gabriel called a “crush of muscle and tuxedos” when a mob of guests stormed the stage.

Most of the insurgents — the type of creatives who brought you the Energizer Bunny, the singing raisins and the Pillsbury Doughboy — grabbed coveted statuettes they hadn’t won.

Although I did not attend the Clio Awards that year, it was the event that began my evolution from seeker of the spotlight to professional recluse. But it was a different event the following year that completed that transformation.

Advertising is like show biz for ugly people, and advertising award shows are our version of the Oscars, a night when minor league celebrities get to dress up in rented tuxedos and borrowed dresses and pat themselves on the back for crafting an amusing headline or a dramatic TV commercial.

Despite my current low opinion of advertising awards shows, there was a time in my career when nothing was more important to me than winning awards. The thought of winning even a single certificate, being recognized by my peers and basking even momentarily in the warm glow of public adulation, was absolutely intoxicating. I wanted to shoot that metaphoric morphine directly into my veins.

The first ad agency in which I was a partner did very well in awards shows, but my second agency became an incredible awards machine. We won awards from all the top regional, national and international shows — the New York Art Directors Club, the One Show, the Print Annual, Best in the West, and we dominated the local shows. Year after year we kicked butt.

One fateful year we won so many awards that it actually became embarrassing. Our art directors and copywriters, the ones who would normally rush up on stage to accept an award and the plaudits of their peers, heard their names called time after time after time that evening. So many times that we all began to feel the icy glares of those in the audience who would have given anything just to win one of the awards we carted off so cavalierly. As our awards piled up, we could feel the audience’s early admiration gradually turning to animosity. Late in the evening, it finally reached the point that when the master of ceremonies once again called out, “And the winner of the gold is dGWB,” but no one from our agency wanted to go up on stage to accept the award.

“You go up,” the art director sitting on my right said to the copywriter on my left. “No, I went up last time,” the copywriter whispered back. “You go up this time.”

Consider it an embarrassment of riches. It was the opposite of the humiliating Clio Awards Show described at the top of this story. Far from stealing awards they hadn’t earned, our people refused to go up on stage to accept awards to which they were entitled.

These two events — one occurring on the east coast and the other on the west coast; one at which I was absent and the other at which I was present; one at which losers exhibited their worst instincts and the other at which winners demonstrated their best; one at which losers were shameless in their failure and the other at which winners were shamed by their success — came together to change the way I approach advertising and life.

I had an epiphany. I realized that the whole advertising awards process was, in the words of radio comedian Fred Allen, one of my heroes, nothing but a treadmill to oblivion. What was once so important to me became meaningless almost overnight.

Enough was enough. I went cold turkey. Not only did I stop entering awards shows, I went home and filled my trash can with almost all the awards I had piled up in the past.

I used the caveat “almost” because I kept only a few that were particularly meaningful to me — the first major award I ever won for a TV commercial (ironically, a Clio Award), the first Best of Show award I ever won, and in order to remind myself of how unimportant awards really are, I also saved one on which my last name was misspelled. They are all gathering dust somewhere in my attic.

I now have just one award displayed in my office. I find it particularly significant because rather than being an award for creativity, rather than being something given by an international judging committee, it is an award created by and given to me by a client to commemorate the remarkable effectiveness of the ad campaign we created for them.

And that’s what advertising awards should really be all about — the clients’ success.

As a result of my self-imposed anonymity, I have a dear friend who jokingly refers to me as “Advertising’s answer to J.D. Salinger.” He says it not because my talents compare in any way to Salinger’s — it would be a joke to say they do — but because like Salinger I walked away from a world of relative well-knownedness and embraced a world of relative obscurity.

Here’s how The American Conservative describes Salinger’s retreat from public life. I can relate:

… Salinger, a tortured minor genius, who, having carried off the highest honors available to a newspaperman, turned from the admiration that haunted his steps and sought for a better and quieter satisfaction in secluded work around the Cleveland suburbs.”

Again, I in no way attempt to compare myself to Salinger, except for where our thoughts intersect on this particular issue.

“It is my rather subversive opinion,” Salinger wrote, “that a writer’s feelings of anonymity-obscurity are the second most valuable property on loan to him during his working years.”

To which I respond, “Ditto.” (Proving once again that I do not compare to Salinger.)

Some other advertising professionals have taken me to task and said things like, “Sure, you can walk away. You don’t need to win any more awards because everyone already knows who you are.” I cannot deny that there is an element of truth to that statement.

Clients I don’t know continue calling. Interesting work keeps coming through the door. If a project sounds interesting, I might take it. It it doesn’t, I won’t. I am fully aware that this is a luxury most advertising, marketing and digital publishing professionals dream of, but never achieve. And I am grateful.

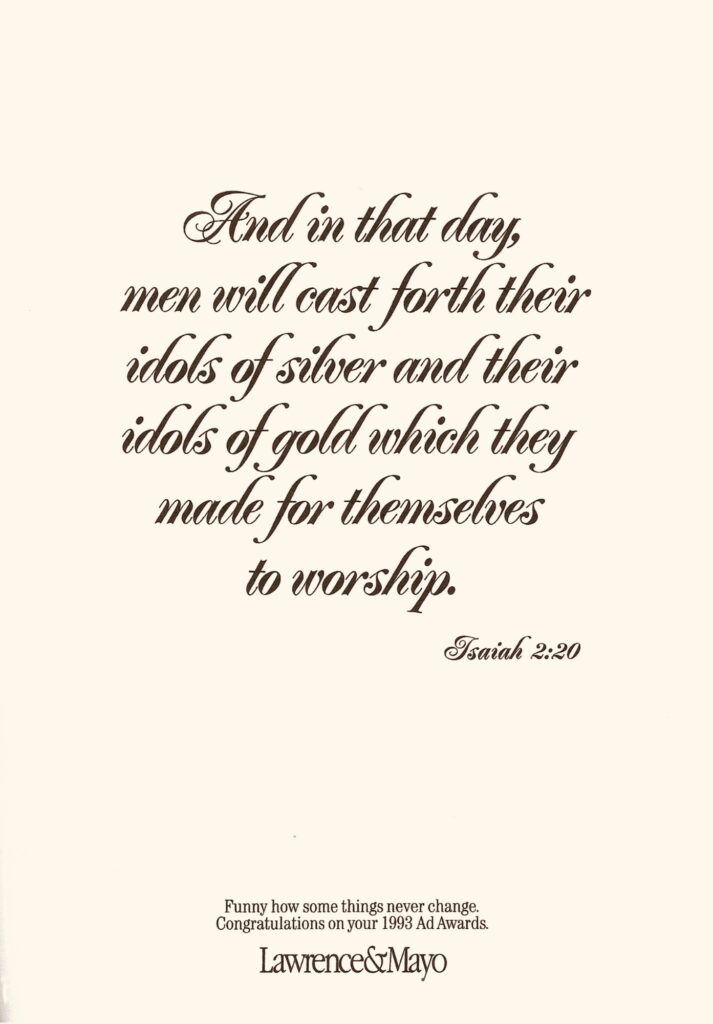

Another very good friend, one of the most talented advertising art directors with whom I ever had the pleasure of working, created the ad shown (above). He was also a winner of many awards, yet he brazenly poked his peers in the eye by paying a pretty penny to run this full page ad in one advertising competition’s awards annual.

I thought it was a brilliant way to point out the hypocrisy of it all, the silliness of it all, the unimportance of it all.

I don’t know if he ever won any awards for this ad, but I do know that when God is your client and Isaiah is your copywriter, the odds are in your favor