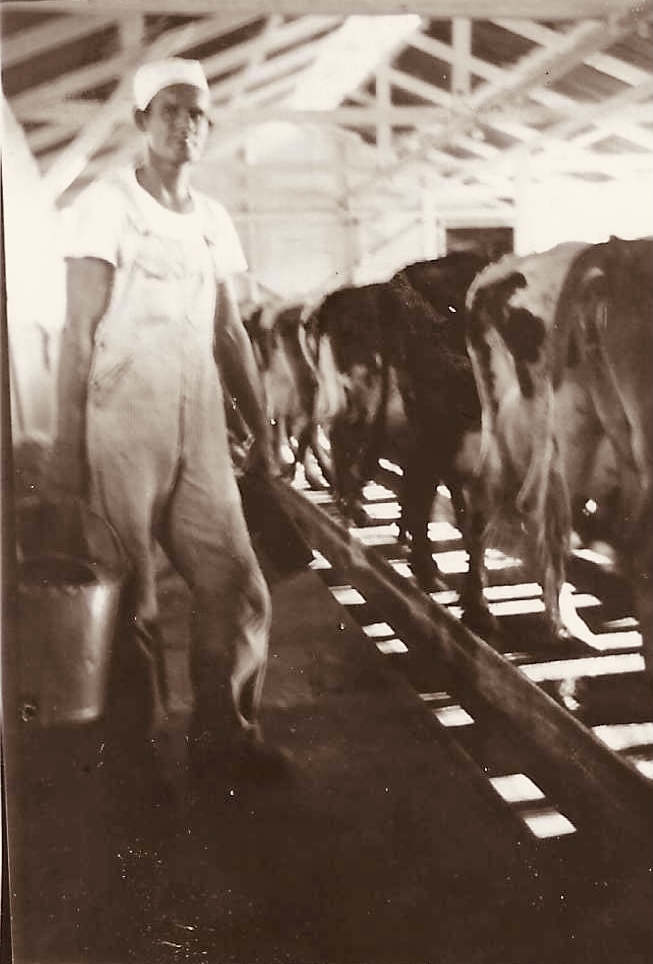

About five minutes after this photo was taken, my dad finished milking one cow and took one step backward in preparation to begin milking the next cow when some unsuspected short circuit caused a blue bolt of electricity to arc across the barn. His entire herd of six cows was immediately electrocuted, dropping dead as he stood just one step behind them.

In that split second, he lost his entire inventory, his entire production line, his livelihood, and all his savings. Not to mention 100% of his his bovine buddies.

I don’t know enough about electricity to know why he was spared. Was it because he was wearing rubber boots that provided enough insulation to protect him? Was it because he was standing just far enough away to avoid the arc? Was it pure luck of the draw?

Whatever the reason, it triggered a family financial crisis. My parents were forced to do something they were absolutely loathe to do — borrow money from the bank to buy six new cows.

I cannot imagine how it was possible to make enough money to live off the milk from so few cows, but they did it. And they had enough money left over to save up to buy another cow and then another and another and they eventually ended up with a herd of one hundred and fifty.

Every cow, just like every person, has its own unique personality. Some are sweet and gentle, others are mischievous, others are just plain cantankerous. When your entire herd consists of only six cows, you get to know each of them pretty well. And vice versa. They must fall on a scale somewhere between pets and co-workers. Maybe you even give them names. But when you milk hundreds of cows, you probably don’t have time to notice each animal’s individual quirks. You eventually get to the point where numbers become more efficient than names so each cow’s left ear gets tagged with an easy-to-read ID.

I am tempted to say my dad was a hard-hearted businessman who viewed each cow as nothing more than a unit of production, and when that cow no longer produced enough milk she was shipped off to a bovine retirement village. But he had one cow he just plain liked. He kept her long after her most productive days were over. He could never explain why. He’d just say, “I don’t know why I keep her. I just like her.” It’s kind of like why the Dodgers keep Clayton Kershaw on the team. They know he’s not the greatest pitcher in baseball anymore; they know he won’t lead the league in wins; and they know he’s lost a couple miles per hour off his fastball. If asked why they continue to pay Kershaw $30 million per year, Dodgers President Andrew Friedman might say, “I don’t know why we keep him. We just like him.”

One year one of my high school buddies (we’ll call him Tim primarily because his name was Tim) begged my dad for a weekend job. My dad laughed at Tim and told him he was a city boy who wouldn’t last one shift with the cows. But Tim was persistent so my dad finally relented and gave him the job. I, who since I was a little boy had been doing the job for which Tim was hired, was tasked with training him.

Tim showed up at 4:00 a.m. for his first shift. I showed him how to bring fifteen cows into each side of the barn. Cows are not the smartest beasts, but they all learn quickly that they will be rewarded if they walk into the barn and stick their heads through the stanchions. I showed Tim how to pull the lever that closed the stanchions, trapping the cows in the spots where they’d be milked. Although it seems counterintuitive, the cows are happy with this arrangement for several reasons. First, the barn is warm in the winter and cool in the summer. Second, every time they are herded into the barn, they’re given the tastiest food of their otherwise dull dietary lives. And third, the milking machines relieve the painful pressure they feel from carrying so much milk. It’s a win-win-win situation for the cows so they line up in the holding pen at milking time, each one eagerly awaiting her turn. (And to expand the every-cow-is-different theme, some cows are the first in line every morning and afternoon and others are recalcitrant and always wait until the very end.)

After closing the stanchions on the first group of fifteen cows, Tim’s next assignment was to wash them, using a pressure hose to clean all the mud and cowshit off the cows prior to them being milked. But the city boy had never really been around cows and didn’t have a clue how to begin.

I demonstrated the proper washing technique on a couple cows, pushing my way in between them to get at the hard-to-wash spots.

He looked at these huge beasts, suddenly realizing how big they were, and with real concern asked, “Don’t they ever kick you?”

“I”ve been doing this since I was a little boy,” I told him. “And I’ve never been kicked.” It was true.

I handed him the pressure hose. He began by spraying the water from a safe distance beyond the reach of the cows’ hooves. “That won’t work,” I instructed him. “You need to get in closer.” He nodded his head and nervously moved in a little closer. I honestly believe the cows sensed his fear. The cow on Tim’s left quickly took exception to his amateur hosing technique, pivoted its right rear leg forward, and then let loose with a hell of a kick that, unfortunately, struck young Tim right square in the portion of the body in which men least want to be hit. He fell to the ground doubled over in excruciating pain, rolling around on the wet, shit covered floor of the barn. He was my pal, so I, of course, found his pain absolutely hysterical. I was laughing so hard I could barely finish washing the rest of the cows while he writhed in agony. Seriously, he had been on the job for only five minutes before suffering an injury I had never experienced.

As you might expect based on this inauspicious beginning, Tim’s career as a farm worker was not a long-lasting one. He gave notice as soon as he could line up a different job that didn’t include the prospect of being booted in the balls by a 1200-pound bovine. But he left behind a legacy. The city boy thought pets should be named, and he could not get it out of his head that the dairy cows were not pets.

”Why don’t they have names?” he asked.

“There are too many of them,” I responded. “They have numbers instead.”

”What about that cow your dad likes. Doesn’t she have a name?”

Tim kept up this line of questioning for the few remaining weeks he kept the job. It got to the point that I was tired of hearing him prattle on about it. So I took a big red paint stick that we used to mark the cows and began writing names on the their right hindquarters.

“Wilma! Bessie! Gertrude! Bertha! Harriet! Edith! Margaret! ” When I ran out of old-fashioned women’s names that seemed appropriate for cows, I began putting our classmates’ names on the cows. “Joyce!” Linda! Nora! Susan! Patti! Veronica! Lee!” Then I moved on to silly nicknames like “Poopsie! Dollface! Babycakes!”

“What the hell are you doing?” my dad asked. He clearly thought I’d lost my mind.

”Tim thinks the cows should have names so I’m giving them names.” Eventually I was able to put names on all 100 milk cows before Tim came back for his final weekend shift.

He got a kick out of it. But not the kind that made him roll around in agony.

I love this part: ” He was my pal, so I, of course, found his pain absolutely hysterical.”

I was watching a Dodgers playoff game last September when the other team’s catcher took a fastball to his … uhhhhh … his groinal-area. He was writhing around on the ground near home plate and every other player on the field and in the dugout was laughing. I do believe it’s a universal man-trait.