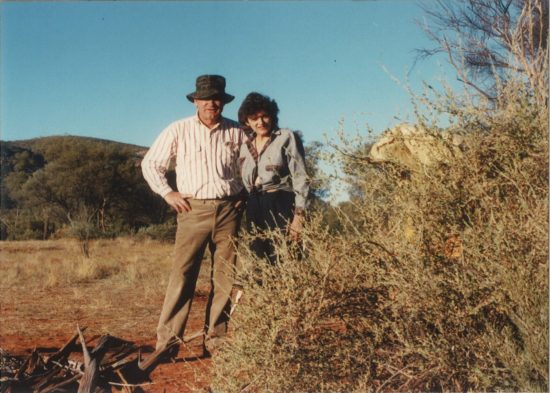

Our friends John and Margaret Rutter have lived in the same beautiful old home, two doors up on the other side of French Street, for more than fifty years. They met in medical school and will celebrate their 60th wedding anniversary in just a few weeks.

Margaret was a country doctor who worked for the state of South Australia, traveling from one isolated country town to another to care for children who wouldn’t otherwise have had any medical care. John was the village doctor here in Angaston for fifty years. He knew everyone — poor and rich and incredibly rich and literally knows where all the bodies are buried.

On one hand, he has a wonderful, dry, understated sense of humor. For example, on a drive past the local cemetery, he gave a little nod toward the headstones and said, “Most of those people were my patients.”

On the other hand, he is a born poet. He allowed us to read his “narrative” (most people would call a it a book, but he insists on the much plainer terminology) which is filled with fascinating stories about his deep, enduring love for three things — the village he lives in, the outback he lives near, and the woman he lives with.

I found this lovely description of Angaston, his home for more than fifty years, on page 117 of his narrative:

I mused with pleasure on my home. A sleepy town, nestling in green covered hills, where we searched for mushrooms in the autumn, and fished for perch in the streams during winter.

Where we walked over the hills all year round, revelling in the cold and wind of winter and the sun and heat of summer, where the flowers of spring and the rich colours of autumn stood firm against the frenetic assault of the media, the ever increasing restrictions of governments and the heartless rigidity of the bureaucracy.

Where the inhabitants floated happily along on a sea of wine allowing enough to be absorbed to make their hearts strong and to bring a healthy glow to their complexions.

I had observed that the longest lived of the inhabitants had two things in common – they loved their gardens and they loved their wine. They talked long and earnestly about their wine and just as long and earnestly about their carrots and beans and lettuces and roses and sweat peas.

They claimed that red wine was the best drink and pigeon manure the best fertilizer.

They loved their music and they loved their sport – but above all they loved their churches and on the Sabbath the bells were rung loud and clear – proclaiming their faith to the world.

And out of all these things emerged a natural generosity of body and spirit that welded the community together, and therefore it flourished in the unique way of so many Australian country towns.

While we’re at it, let’s include his description of his lifelong love affair with the Outback:

To the north and south ran our sand hill, to the east were endless lines of parallel sandhills, and to the west was a blurred nothingness, on which the only recognisable feature was our vehicle, looking tiny and vulnerable, and beside it our fire, a minute speck of flame from which a cotton thin thread of smoke went straight up to disappear in the heavens, undisturbed by even the faintest touch of a breeze.

The panorama, to all points of the compass, was huge, stark, somber, deadly, and yet magnificent.

I felt small, but secure, surrounded by nature in all her rawness — bare, unclothed, uncluttered.

For a brief moment I experienced a flash of understanding of how the aboriginals felt about their land.

For them it was all things, all powerful, omnipotent, permanent, mysterious. It giveth and it taketh away, and they are a part of it.

I could feel the strength of the land around me, its power and its incorruptibility.

When changed by man it slowly and remorselessly rids itself of him and then just as remorsefully returns to its natural state.

I looked at our footprints on the sand. Soon the air would move and they would be gone forever and there would be no trace of our passing…

I walked steadily for a couple of kilometers and then sat down amongst the gibbers and took in the scene around me.

The plain seemed almost endless, and was scattered with millions of small brown gibbers, all showing the effects of the intense heat they had been subjected to over tens of thousands of years.

The land was motionless, there was no sound, the air was still. There was no sign of life — not a bird nor a blade of grass, just countless shimmering stones.

The pale blue sky was devoid of cloud and covered the land from horizon to horizon like an immense blue umbrella. As I watched the sky it seemed to come closer and closer until I felt that I could put up my hand and touch it.

Once again I felt the prodigious power of the land. Its strength seemed to ooze into me, giving me a feeling of contentment and calm.

And then, of course, John devoted a few words to Margaret, the woman he’s so devoted to:

I had met her in a zoology lecture during the first year of our medical course and had been immediately smitten and we had married soon after our final exams. I had become progressively more smitten as the years rolled by. She was christened Margaret but most of our friends called her Agatha. I was never sure why.

“What are you thinking about?” she said.

“I’m wondering why we are sitting up here at three in the morning drinking a stimulant.”

“Do you feel stimulated?”

“Yes, how about you.”

“Me, too,” she replied, taking me by the arm and leading me back to the bedroom.”

Oh, for God’s sake, John. You had me hooked on your sweet, tender love story and then you went all soft core porn on me.

Despite this unexpected detour off the main road of his narrative, Jamie and I are truly honored that John allowed us to read his reminiscences.

And we’re even more honored to call John and Margaret friends.

Eloquent and heartfelt.

I want to move there!

Ha! You finally met a better writer than you….

And on top of that, he could remove my appendix. Dr. John wins.

Or a sigmoidoscopy ????????????